As white, female mathematics teacher educators (MTEs) in our initial years as tenure track faculty, we recognize both our positionality and the urgency required in our pursuit of becoming anti-racist MTEs. Brought together by an Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators’ (AMTE) STaR Research Interest Group centered on teacher knowledge and beliefs, we have recently spent time unpacking and reflecting on AMTE’s Statement on Systemic Racism, specifically the call “to act in ways that are anti-racist and to critically examine [our] own practices and the potential biases implicit within them” (2020, p. 2). To accomplish this, we recognize the necessity of relinquishing our white privilege, while simultaneously better-equipping ourselves to enact anti-racist teaching. Thus, we began to call out our racist practices and admit to having been “color blind” (Bonilla-Silva, 2006), a behavior perpetuating the systemic barriers for not only our Black students and colleagues but also our society as a whole. We recognize we cannot and should not use our discomfort or ignorance to avoid these critical conversations. Otherwise, we impede our students and colleagues and inadvertently protect the current racial hierarchy.

As MTEs with expertise in teacher knowledge and beliefs, we recognize this as our lens for initiating action. From that basis, we know that to change our practices we need to use this specialized lens to reflect on our own practices, recognize how our portrayed narratives function in our current conversations, and ultimately take actions to personally and professionally change and interrupt racism. As we initiated this journey of self-analysis, we drew from the noticing and wondering framework (Smith, 2009) as a powerful tool to address the multi-faceted dimensions required to “strengthen [our] own ability to see and to act in ways that are anti-racist” (AMTE, 2020, p. 2). Here we describe our intentional use of a notice-wonder protocol (Venables, 2011) to critically examine AMTE’s Statement on Systemic Racism (2020) in terms of the personal and professional calls to action. This protocol promoted a cyclical and non-judgmental examination process as we noticed specific assertions within the statement, wondered how those assertions differed from our current practices and beliefs, and then through collaborative discourse further noticed other assertions within the statement that helped us move from acknowledgement to action (NCSM & TODOS, 2016) as MTEs committed to promoting anti-racist teaching.

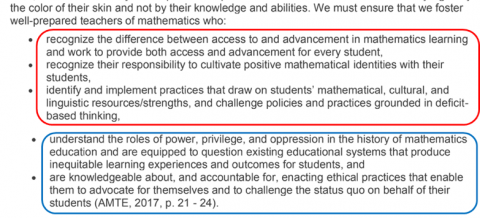

As we unpacked the calls for action in the position statement using the noticing-wonder protocol, we noticed the first three bullets (see Figure 1) were practices we frequently promoted as MTEs, prompting us to wonder why these felt so comfortable. We realized these items could largely be addressed through equitable teaching practices (e.g., open tasks, heterogeneous groups, student-centered discussions, formative assessments), which are often promoted as beneficial practices for all students. We paused and wondered if this was an example of interest convergence, defined as when “potential benefits to the collective Black are metered by Whites and White design and are contingent on parallel benefits to Whites” (Martin, 2015, p. 21). These wonderings lead us to a key realization that our comfort and understanding of the value of these practices aligned with the “All Lives Matter” argument. That is, as we promoted these practices as beneficial for all students, we were not explicitly considering the specific needs of Black students.

As we continued to notice and wonder together, we found the final two bullet points (see Figure 1) were not nearly as comfortable. We noticed that we could no longer take refuge behind interest convergence, but instead must unpack power, privilege, and oppression to prioritize the needs of our Black students. We wondered, for us, if this is where anti-racist teaching begins. While the first three bullets provided lenses for interrogating mathematics education, without the final two points interest convergence could be a motivator. We noticed as we unpacked the position statement, we were pushed as MTEs to no longer advocate for changing the way we teach mathematics because it will benefit all students, instead we must intentionally consider instructional practices through the lived experiences of Black students. For us, this provided a beginning point for becoming anti-racist MTEs, interrogating the source of our discomfort, questioning our white privilege, and centering Black students’ experiences in mathematics classrooms.

Figure 1. AMTE Standards of Practice identified within AMTE’s Position Statement (2020)

Throughout the position statement, we noticed the premise of dismantling systemic racism through working to develop a generation of anti-racist teachers. We, as MTEs, must strive within our own contexts to develop these understandings in our local teachers, which requires enriching our own understandings. To unpack the understandings the position statement is asking of us and the teachers we educate, we continued noticing and wondering about individual assertions in the document, such as well-prepared teachers “are knowledgeable about, and accountable for, enacting ethical practices that enable them to advocate for themselves and to challenge the status quo on behalf of their students” (AMTE, 2020, p. 2). We, as MTEs, must continue developing this knowledge of ethical practices and their potential for dismantling oppressive systems. However, this is not sufficient. Both this individual assertion, and the overall position statement, demand accountability and action. We must educate teachers about these practices and how to enact them in ways that affect change. We must become knowledgeable of our local contexts, both of our teacher preparation programs and our communities. We see this statement as a targeted destination by which we set our mathematics instructional roadmap, both within and across programs and courses. Instead of viewing AMTE’s social context standards referenced in the statement as an addition to the other mathematics teaching and learning objectives, we noticed a call for MTEs to reset other instructional goals as building toward the development of these potentially powerful practices within mathematics classrooms.

In our readings (e.g., Gutierrez, 2013; van Es et al., 2017), we noticed that descriptions of what teachers do to effectively bring about change are situated within the specific racial, socioeconomic, and power dynamics at play with the focal context. MTEs’ work, then, is to develop teachers who can enact ethical mathematics practices that elevate Black students within their own communities. This requires MTEs to develop contextual knowledge of local school districts, which led us to wonder: What do ethical mathematics teaching and learning look like in our individual contexts? What systems need to be challenged across our school-university partnerships (e.g., tracking and standardized testing)? How can we empower teachers and students to use mathematics to understand, address, and deconstruct current inequitable systems? Who are the local anti-racist organizations? What relevant professional development are teachers receiving?

We recognize there is no end to the work of unpacking and acknowledging our implicit biases and the racism we perpetuate. Since we are acting individually within our local communities, we also wonder how we will contribute to the organizational (e.g., AMTE) and broader societal levels? How can we engage with others in enacting this work? We recognize the tendency to fall back on practices that are comfortable, safe, and familiar. We cannot allow this backward movement because when we do, Black students are not safe and social injustices are perpetuated. The position statement of the National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics and TODOS: Mathematics for All (2016) suggests anti-racist disruption is propelled by acknowledgement of unjust systems, action toward transformed policies and practices, and accountability for sustained commitment to maintaining social justice as a mathematics education priority. Our acknowledgement broadened as we used the noticing and wondering framework to unpack statements on systemic racism, as well as our own perspectives. Collaborative noticing and wondering not only promoted individual critical reflection, but also encouraged collective professional discourse and dialogue. The noticing and wondering framework helped us envision actions we can take to move from pedagogically sound teaching focused on legitimizing individual student’s cultural strengths, knowledge, and ways of learning, to anti-racist teaching focused on unveiling and addressing systemic barriers that impede Black students’ access and opportunity (Galloway et al., 2019). We wonder how AMTE and its members can help us in collectively acknowledging unjust policies and practices and our role in perpetuating them. How can we work together as MTEs to make AMTE’s position statement a living document that will promote transformative action? How can we hold each other accountable for continuous examination of the impact our actions have on our Black students and colleagues?

We recognize we are not trailblazers in this work. We value the work of others before us. We share what we are doing to hold ourselves accountable and to invite others to help us create a space to continue our shared work as the “we” called by AMTE’s leadership to “assume the burden”, “actively work to be anti-racist in our acts of teaching, research, and service” (AMTE, 2020, p. 2), and mutually imagine more equitable possibilities. We, as new members of this organization’s community, wonder how AMTE’s leaders and members can create spaces, perhaps those that are online, for self-study, professional learning, and critical discourse that will enable meaningful enactment of the calls to action in the Statement on Systemic Racism (AMTE, 2020).

References

Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators. (2020). AMTE statement on systemic racism [Position statement]. https://amte.net/files/AMTE%20Racism%20Press%20Release.pdf

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Roman & Littlefield Publishers.

Galloway, M.K., Callin, P., James, S., Vimegnon, H., & McCall, L. (2019). Culturally responsive, antiracist, or antioppressive? How language matters for school change efforts. Equity and Excellence in Education, 52(2), 485-501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2019.1691959

Gutierrez, R. (2013). Why (urban) mathematics teachers need political knowledge. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 6(2), 7-19.

Martin, D. B. (2015). The collective Black and principles to actions. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 8(1), 17-23.

National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics and TODOS: Mathematics for ALL. (2016).

Mathematics education through the lens of social justice: Acknowledgment, actions, and accountability. [Position statement]. https://www.todos-math.org/assets/docs2016/2016Enews/3.pospaper16_wtodos_8pp.pdf

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2014). Principles to actions: Ensuring mathematics success for all (6th ed.). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Smith, M. (2009). Talking about teaching: A strategy for engaging teachers in conversations about their practice. In Empowering the mentor of the preservice mathematics teacher (pp. 39–40). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

van Es, E.A., Mercado, J., & Hand, V.M. (2017). Making visible the relationship between teachers' noticing for equity and equitable teaching practice. In Teaching noticing: Bridging and broadening perspectives, contexts, and frameworks (E.O. Schack, M.H. Fisher, & J.A. Wilhelm, Eds.). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Venables, D. (2015). The case for protocols. Educational Leadership, 72(7). Retrieved November 4, 2020, from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/apr15/vol72/num07/The-Case-for-Protocols.aspx

Venables, D. (2011). The practice of authentic PLCs: A guide to effective teacher teams. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Authors’ note: The authors are listed in alphabetical order and equally contributed to the article.