It is known that the STEM pipeline has a few leaks. One potential patch to the STEM pipeline is at the community college who have students that often transfer to four-year universities (Fauria & Fuller, 2015). Students who transfer to four year schools and pass the first semester are slightly more likely to graduate with a STEM degree than students who started at the institution (Laanan, 2001; Myers, Starobin, Chen, Baul, & Kollasch, 2015). However, transfer shock remains a hurdle. Many students have a significantly lower GPA in the first semester following transfer. There is evidence that increasing students’ sense of classroom and cohort community can reduce transfer shock (Fauria & Fuller, 2015), but research has dealt little with transfer pre-service STEM teachers.

Even though about 60% of all undergraduates will transfer credit from at least one class to another institution, transfer students are an understudied population (Fauria & Fuller, 2015; Hagedorn, 2005; Wang, 2009). Transfer shock, the dip in grades following the transfer from a two-year to a four-year institution, can largely affect whether students pursue their STEM degree after transferring (Fauria & Fuller, 2015). One way to increase the likelihood of transfer students completing their degree is getting them to participate in classroom discussions and being an active group work participant (Fauria & Fuller, 2015). In order to get students to participate actively in their groups, we incorporated Smartpens into our study.

Livescribe Smartpens haven’t been researched much other than in the context of an instructor using them within a flipped classroom context (Baker, Czocher, Tague, & Roble, 2013; Fisher & Raines, 2014). However, when used, these Smartpens can enhance a flipped classroom experience for students and work as tools for review (Baker et al., 2013; Fisher & Raines, 2014). In the context of our study, we provided Smartpens to the students both as tools for us and the students.

Our study consisted of seventeen pre-service teachers transferred from seven different community colleges. Because of this, most of them did not know each other. Due to the different experiences in their previous math courses from different colleges, this math education course provided an opportunity to develop a community among a group of pre-service teachers that move throughout their degree as a cohort of students. Assigning one Livescribe Smartpen per group of students and reinforcing the worth of group work for the course grade enabled us to drive students to participate within their groups.

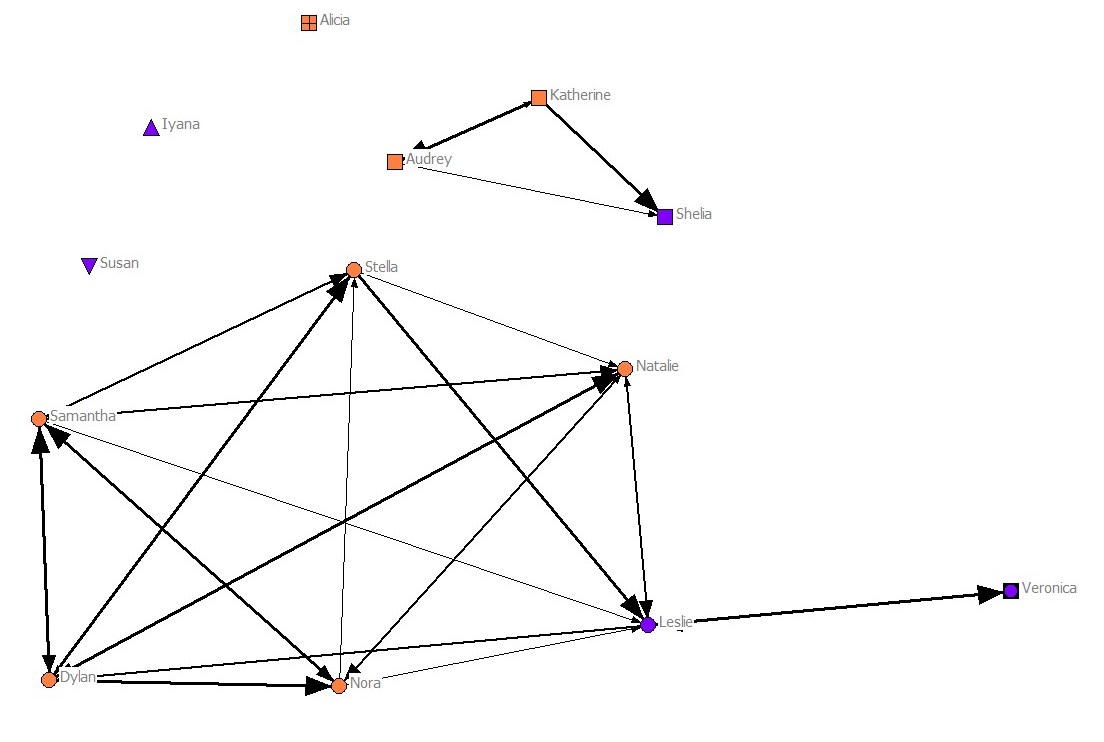

For the first quarter of the semester, the seventeen pre-service teachers were split into four groups. Each group received a group notebook that would hold all their responses to the assigned in-class problems. Additionally, each group received a Livescribe Smartpen to be used to record their answers. We argue that limiting each group to one notebook and one actual person to write the final answer to be graded helped push students to discuss the math and build a classroom community. In fact, at the beginning of the Fall 2015 semester, Figure 1 shows how weak the social network was among the class, whereas Figure 2 shows an obvious increase in the number of connections between students and their strength, as indicated by the thickness of the lines (Dibbs, Rios, & Beach, under review).

Figure 1. Initial pre-calculus social network

Figure 2. Cohort social network at the end of the course

It is evident that the pre-service teachers developed a sense of community throughout the time spent together for the class. The experiences of the students towards the classroom community can be summed up in a quote:

Sure, I had classes with [the other students from my community college] before this class. Samantha was in my spring classes, and we all took the same [Child Psychology] classes together that semester. That doesn’t mean I knew anyone. Most of the time, we could pick our groups. I worked with Natalie, and so I knew her a little, but not really anyone else. (Dylan, December)

One of the major reasons stated by students when asked what factors created stronger cohort bonds was the group grading conducted in the pre-calculus class. Upon further explanation, it challenged students to break down their reluctance towards communicating with other group members and gave students a sense of responsibility for their peers’ grades:

I didn’t know anyone when I started in the fall. And I don’t like to talk in class. In other classes, I usually don’t answer questions, and in group work, I hang back. In pre-cal, I couldn’t do that. Since there was only one notebook, it didn’t matter what I knew. It was what we knew. (Alicia, May)

For any in-service teachers that wish to build a classroom community within their respective classes, a flipped-classroom method incorporating group grading as was done in this study could serve to be useful. Of course, there exist struggles when incorporating new methods into a course, so next we provide some recommendations on implement group learning/grading and Livescribe Smartpens.

Recommendations

An important dynamic of the classroom in the study was that it centered around group learning. A sense of community developed as the pre-service teachers discussed the class material with one another during class and after class. We found that groups of students at similar ability levels formed the strongest relationships within the social network and thus believe students at similar ability levels to work best together. This is further supported by the students reverting to working with these partners in the subsequent spring semester. Students reported that the most motivating part of group learning was the group accountability. 75% of students reported that they would have quit on an assignment sooner if there was no group grading. Because of this, we also suggest incorporating group grading as a motivator for students to participate in their groups.

The Livescribe Smartpens are pens that record audio and match it in real-time to what is being written on the special paper ($3 for a 1 subject notebook from Livescribe). The older model Smartpens range at about $100 a pen and work as a feasible tool for group facilitation. The pens are pretty intuitive to use and shouldn’t take much longer than an introduction at the beginning of the semester for students to understand them. When using Smartpens, groups of three or four students seemed to be the optimal size, any groups larger than that had trouble sharing the notebook. We also suggest creating a system to assign a recorder so that all students share the task. Since we had the notebooks stay in class, some students avoided being the recorder because they did not want gaps in their notes since they were busy recording instead. Assigning the recorder role in rotation and encouraging students to take pictures of the work in the notebook helped ameliorate most complaints. Additionally, make the Pencasts (the .pdf files found on the Smartpen from plugging it into a computer) available to students. Consider the statement made by Natalie:

Man, you know I’ve had pre-cal before. Even saved my notes form high school. But when I look back on them…it’s gibberish. At least when I listen to the Pencast later, I know there is some hope I can learn from what I know now then. (Natalie, May)

The Pencasts had value to the students since they provided a resource for the students to review before exams. In order to make these accessible to the students, we suggest using a dedicated Dropbox account to post Pencasts. Each student should have a personal folder, and the only Pencasts uploaded to their folder should be the ones from that student’s group(s).

Sixteen of the 17 students in this class stayed as a middle school mathematics major after the pre-calculus course, including all of the transfer students. Typically, about 20% of students drop this major at our university within a semester of this course, so this better retention rate is a sight we’re happy to experience. We hope our study sheds more light on group grading and the positive effect of Livescribe Smartpens. Of course, further research is needed to better improve the condition of our transfer students in the STEM fields.

References

Baker, G., Czocher, J. A., Roble, A., & Tague, J. (2013). Successful collaboration among engineering, education, and mathematics. Proceedings of the 2013 ASEE North-Central Section Conference, USA, http://people.cst.cmich.edu/yelam1k/asee/proceedings/2013/papers/23.pdf

Dibbs, R. A., Rios, D. L., & Beach, J. M. (under review). Using smartpens to address transfer shock and classroom community in a flipped pre-service teacher course. CITE.

Fauria, R. M., & Fuller, M. B. (2015). Transfer student success: Educationally purposeful activities predictive of undergraduate GPA. Research & Practice in Assessment, 10, 39-52.

Hagedorn, L. S. (2005). How to define retention: A new look at an old problem. In A. Seidman (Ed.), College student retention formula for student success (pp. 89-106). ACE/Praeger.

Laanan, F. S. (2001). Transfer student adjustment. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2001(114), 5-13.

Myers, B., Starobin, S. S., Chen, Y., Baul, T., & Kollasch, A. (2015). Predicting community college student’s intention to transfer and major in STEM: Does student engagement matter?. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 39(4), 344-354.

Wang, X. (2009). Baccalaureate attainment and college persistence of community college transfer students at four-year institutions. Research in Higher Education, 50(6), 570-588.